Home ownership in Australia is embedded in wealth accumulation, security of tenure and security in retirement. In other words, home ownership in Australia makes life a lot easier in the long run than renting. While surveys indicate most Australians want to own their own home, the latest available data shows only 66% of households do.

As we head into the next election, both the Labor party and the Coalition have included some expansion of the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme (FHLDS) in their policy platforms:

Labor has proposed a First Home Buyer Support Scheme, which will review price caps on a six-monthly basis, and extend 10,000 government guarantees to regional Australian applicants.

The Coalition would also reserve 10,000 home loan guarantees for regional Australians, but would expand eligibility in the regions to non-first homebuyers, and limit purchases to new homes.

The Coalition would also increase the current 10,000 regular FHLDS places to 35,000 per year. The family home guarantee would also be increased to 5,000 places per year, creating a total of 50,000 new low-deposit guarantees in 2022 alone.

How does the scheme work?

In its current form, the FHLDS allows eligible borrowers to take out a mortgage with a deposit as small as 5%, without paying lenders mortgage insurance. This is done by the government guaranteeing up to 15% of the loan.

Applications are limited to singles on an income of up to $125,000, or couples on $200,000. Purchases under the scheme are limited to between $350,000 in some regions, to up to $950,000 in Sydney for new homes.

But whether the scheme is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is a really complex question. Some of the pros and cons of the scheme are outlined below.

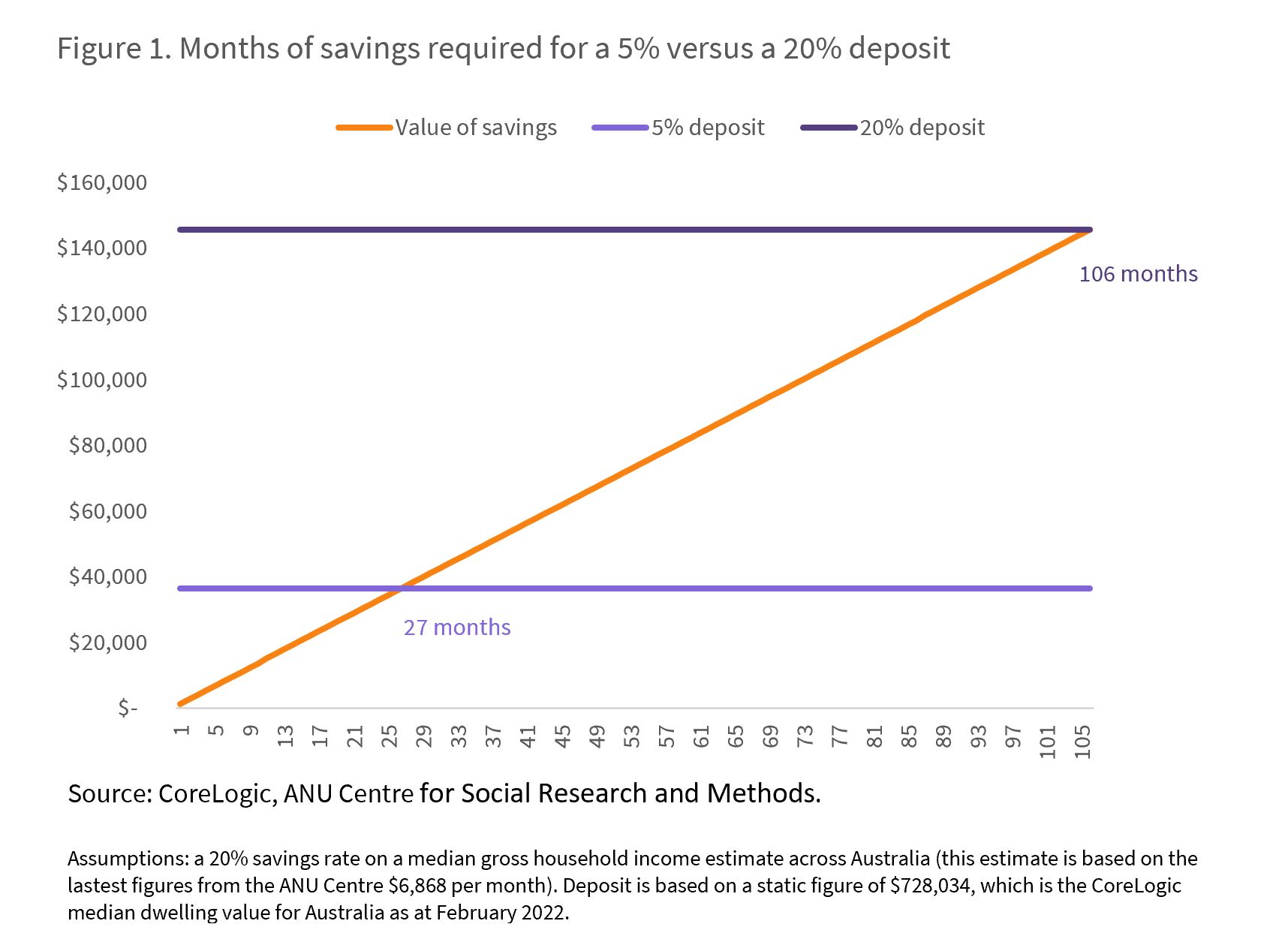

Pro: It (roughly) quarters the time it would take to save a deposit

Based on the median dwelling value across Australia at the end of February ($728,034), CoreLogic estimates it would take around 2.3 years for the median household to save a 5% deposit on a home (Figure 1.0). A 20% deposit, which is the level allowing borrowers to avoid lenders mortgage insurance (LMI), would take around 8.8 years.

This could cut 6.5 years in the rental market, which at current weekly rent values on the median dwelling in Australia, equates to almost $160,000. The savings on LMI could be upwards of $30,000 on the median Australian dwelling value with a 5% deposit.

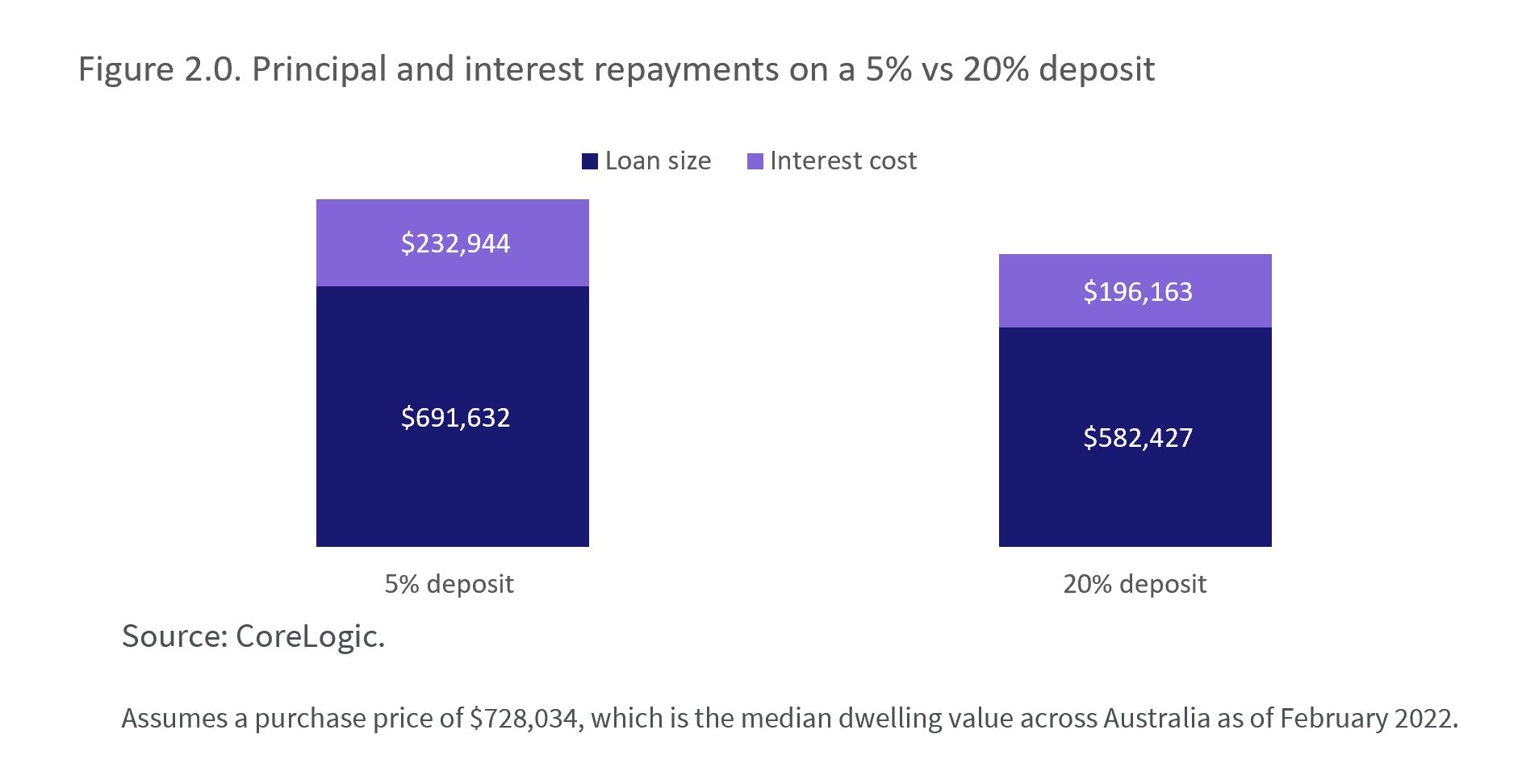

Con: Interest costs would be higher

Understanding the concept of interest is crucial to do a thorough cost-benefit analysis of the scheme. Taking the median dwelling value and the current average mortgage rate for principal and interest owner-occupier borrowers (2.44%), the difference in interest costs between a 5% deposit and a 20% deposit is about $37,000 over the life of the loan (Figure 2).

With the cash rate likely to rise sometime in the next 12 months, this will exacerbate interest between those on a 5% and 20% deposit loan. Understanding interest is extremely important when taking on large mortgages, especially when targeting these schemes to younger Australians and women, where rates of financial literacy among these groups tend to be lower.

While the interest costs on a 5% deposit home loan may be larger, it is important to weight them against the cost of not being in the market. These costs include any increase (or decrease) in purchase prices and the cost of renting.

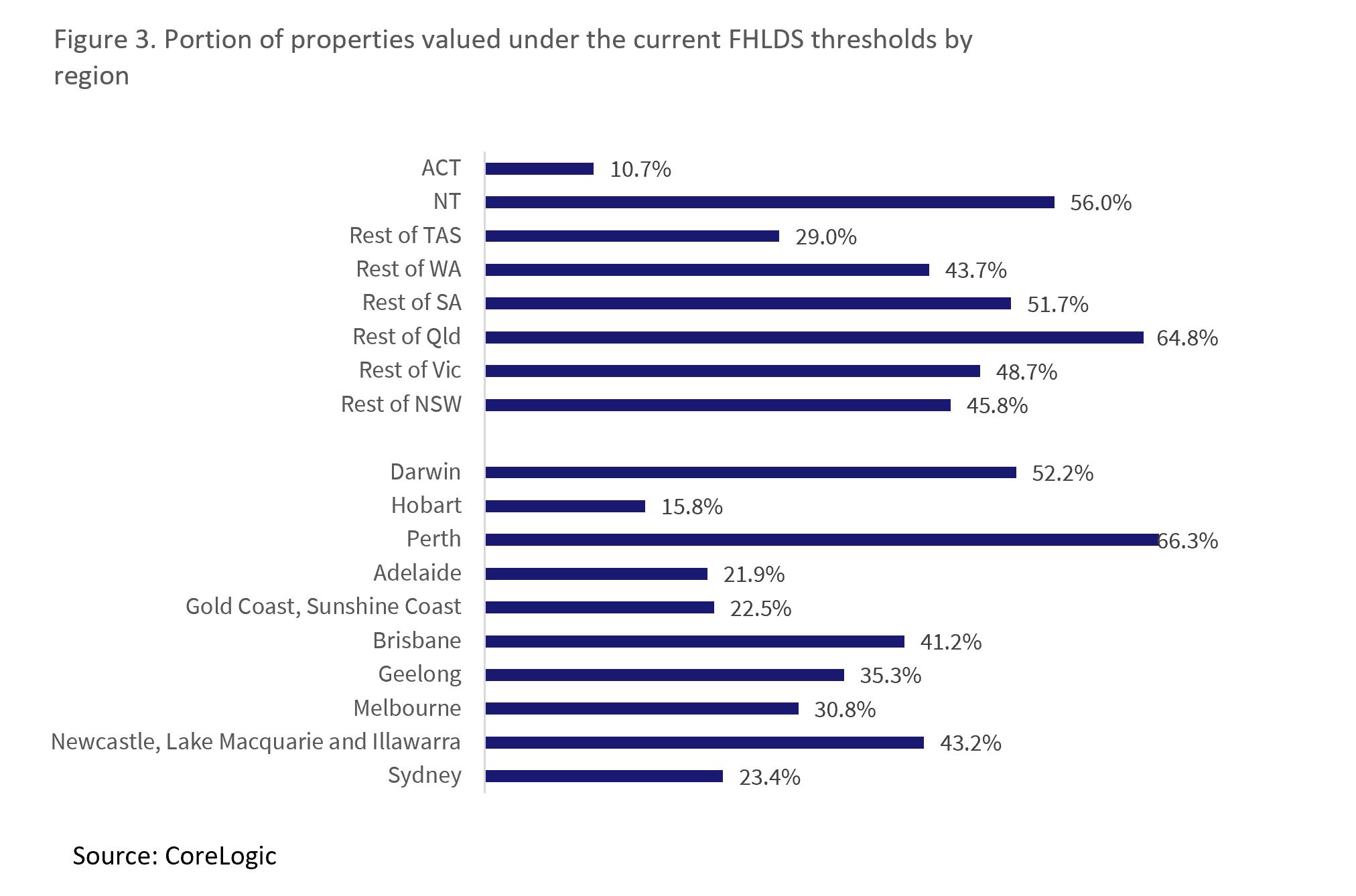

Pro: More than one in three established properties qualify

Based on the scheme’s current price caps for established properties, CoreLogic estimates around 35.4% of Australian dwellings qualify. If prices decline, this could free up more dwellings for applicants, while the reverse is true if prices continue to rise.

Con: Price thresholds are hard to determine

A decline in home values would increase the number of properties available under the FHLDS, however Australia’s rapidly changing and diverse housing market means stock availability varies widely by region.

Figure 3 shows the current portion of valuations that sit under the established purchase price thresholds for the scheme in each region, as at the end of March. CoreLogic’s analysis shows the proportion of qualifying properties ranged from from up to 66.3% of dwellings in Perth, to just 10.7% in the ACT.

Purchasing thresholds have been adjusted higher through the 2021-22 FY, and Labor has noted it intends to review purchasing caps on the scheme on a six-monthly basis, so this policy can be adapted to changing market conditions.

Pro: It’s not a revolution, but it’s pragmatic

The FHLDS is not revolutionary. Where the 2016 and 2019 Federal elections saw Labor campaign on changes to negative gearing and capital gains concessions, both parties are trying to assist first homebuyers in getting over the deposit hurdle, “while protecting the value of homes”.

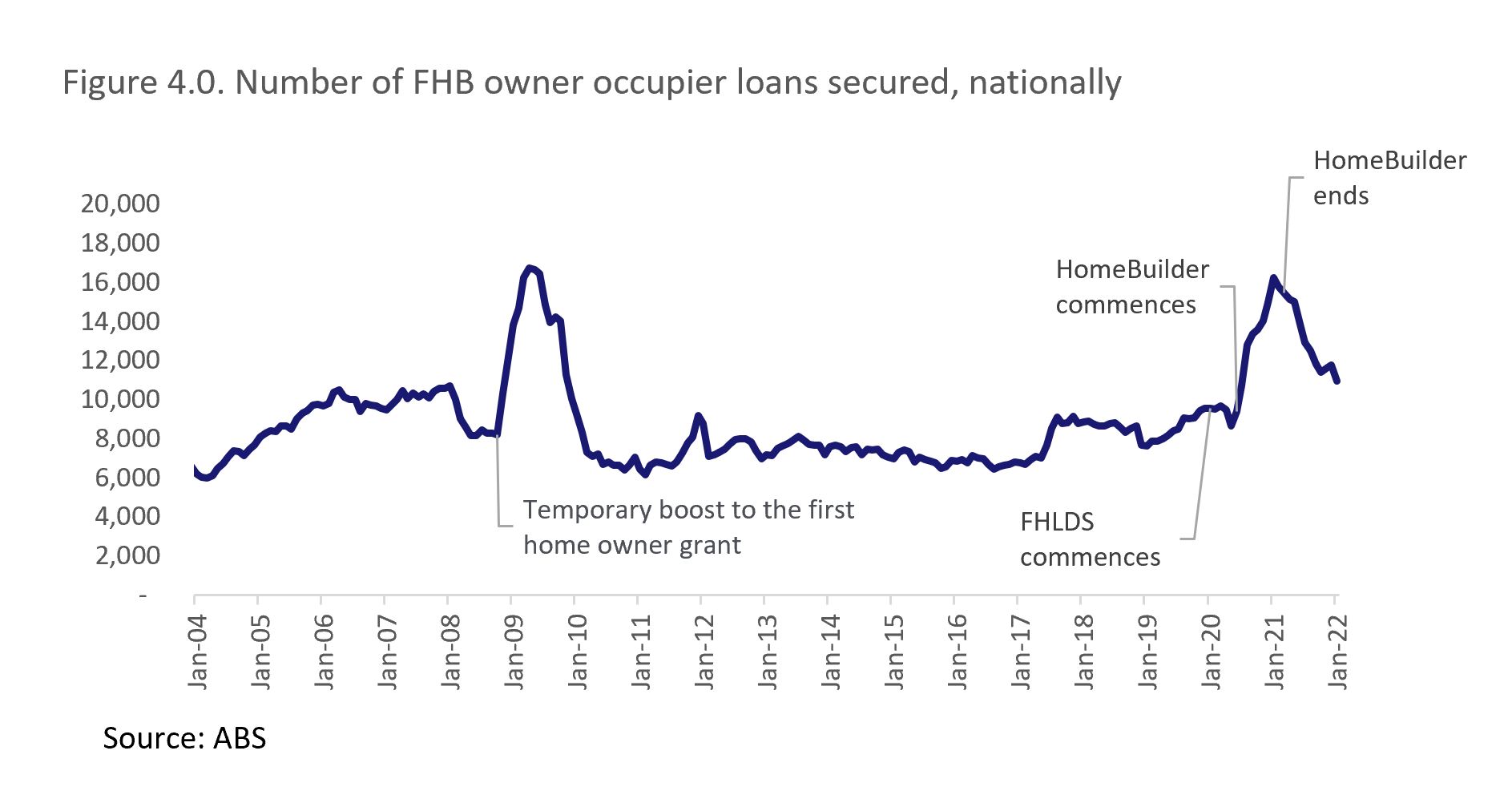

To-date, the scheme has seen very high demand. Within four months of commencement, more than 8,000 places in the scheme had been taken up. ABS data also shows first homebuyer loans surged from the start of 2020 (Figure 4), coinciding with the start of the scheme.

Con: it could do better on the equity front

Australia’s rate of home ownership has declined from around 71% in 1995, to 66% in 2016. But as noted in Grattan research, lower rates of home ownership are associated with lower income. This means addressing low rates of home ownership should target lower income households.

The income thresholds for the FHLDS are relatively high. For example, ABS Household Income and Wealth data showed that in 2017-18, a gross household income of $200,000 per year placed households in the top 20% of incomes, and that median household incomes were closer to $88,000. Couples earning up to $200,000 can qualify for the FHLDS, though figures would suggest their risk of missing out on home ownership without it is lower.

According to NHFIC however, the highest concentrations of guarantees have been below the income thresholds through 2019-20, at $60-$80,000 for singles and $100-$125,000 for couples. The purchase price caps may also have a self-selecting effect, with those on higher incomes seeking more expensive homes.

Pro and Con: It will increase housing demand at a time when the housing market is cooling

Historically, targeted first homebuyer grants have incentivised buyers. Figure 4 shows how the temporary boost to the first home owner grant increased housing activity around the time of the global financial crisis in 2008, when a lift in real estate transactions positively impacted the economy.

Expanding the FHLDS could increase first homebuyer numbers at a time when the housing market outlook is uncertain. Alternatively this could increase demand for more affordable properties, increasing prices in this segment.

A final word on First Home Buyers

Should first homebuyers be worried about the prospect of a falling market? Probably not. The risk of negative equity is mitigated by the fact that owner-occupiers hold their properties for long periods of time, and Australia’s labour market is at its strongest level in 50 years. CoreLogic’s resale analysis shows owner-occupiers have a median hold period of around nine years.

Historic performance in the Australian housing market has shown peak-to-trough declines last an average of 12 months nationally. The RBA also recently produced analysis showing first home buyers were at no greater risk of mortgage arrears than other borrowers. Negative equity becomes a greater risk when mortgage serviceability deteriorates. This is why a thorough assessment of borrowers is so important in an environment where rates are set to rise.

If there is a limitation to expanding the FHLDS, it is probably in the details of refining income and price thresholds, rather than major default risks for first home buyers. Regardless of which political party wins the 2022 election, an objective of housing policy should also focus on more equitable housing outcomes across income brackets, including adequate provision of affordable housing for those who are unlikely to achieve home ownership.