Eliza Owen reviews the 2024-25 Federal Budget hits and misses with housing.

For a Budget that made housing one of its central focuses, the federal government has three big ‘misses’ in the plans laid out on Tuesday night. Our Budget analysis considers what could be done more efficiently in the approach to Commonwealth Rental Assistance (CRA), construction, and use of existing supply.

What did the Budget get right on housing?

Increases in housing and rental costs since the pandemic have been especially hard on low income households. The decline of social housing over time has worn down the buffer between the private rental market and insecure housing, so when rents are rising as strongly as they are now, vacancies are low and demand is high, it’s low income renters who are increasingly vulnerable.

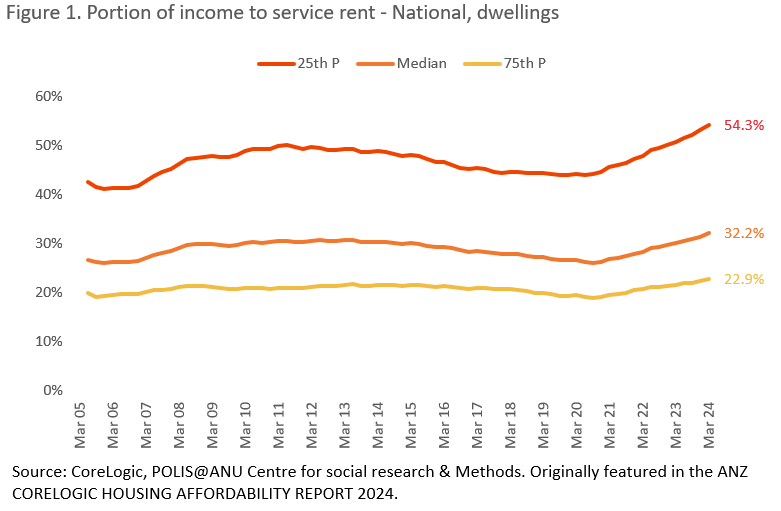

Research from the latest ANZ - CoreLogic Housing Affordability report also showed the low-income end of the spectrum saw the biggest increase in the rent to income ratio in the past four years. In March 2024, the 25th percentile rent value nationally represented 54.3% of the 25th percentile gross household income estimate (figure 1).

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare continued to report increases in unmet requests for specialist homelessness services, which rose to 108,000 in 2022-23, most commonly because there was no accommodation available at the time.

The federal Budget has allocated funding to where it is urgently needed: crisis accommodation, social and affordable housing funding, and a boost to rental assistance for renters receiving other social assistance payments. Housing initiatives in the budget included:

- An additional $423.1 million for the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (taking total funding to $9.3 billion over five years) to deliver public housing and homelessness strategies. This also includes a doubling in funding for homelessness services at $400 million per year to be matched by the states and territories.

- A second-consecutive increase to Commonwealth Rental Assistance (CRA). This $1.9 billion investment over five years will increase the maximum rate of CRA by a further 10%, following a 15% increase last year.

- Additional concessional financing of up to $1.9 billion for community housing providers and other charities to support the delivery of new homes.

- An additional $1 billion targeted toward crisis and transitional accommodation for women and children fleeing domestic violence, and youth.

- An additional $1 billion for the states and territories to help speed up construction on infrastructure to support new housing (i.e., sewers, roads, energy and water infrastructure).

- Around $90 million for training and education to boost the construction workforce.

- A better targeted migration program, with student visa grants tied to the delivery of purpose-built accommodation.

What did the budget miss?

1. Commonwealth Rental Assistance was increased, but not better targeted.

The budget misses an opportunity to optimise CRA payments by ensuring they are well targeted. The productivity commission noted that in 2019-20 (albeit before rent values boomed) that 28% of CRA recipients would still have avoided housing stress without the payment, and 27% of recipients were in the top 60% of household incomes.

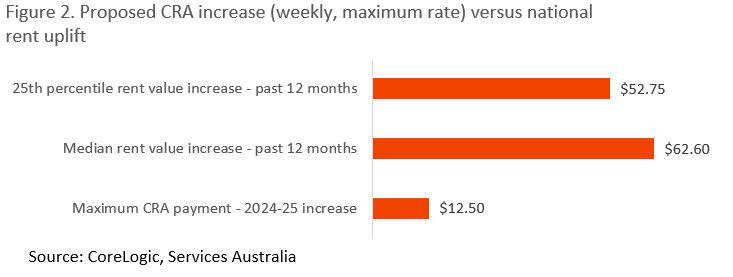

CRA payments vary depending on circumstance, but the maximum rate of around $125 per week means the biggest increase under the budget will be $12.50 per week. As noted in our budget analysis last year, CRA increases offered by the government are very modest in dollar terms compared to actual rent increases in the private rental market.

Figure 2 shows the maximum proposed 2024-25 increase to weekly CRA, against actual rent increases at the median and 25th percentile rent value across Australia in the year to April 2024.

A broad-based boost to CRA for those already receiving it is a pretty efficient way to ensure those in more vulnerable positions in the private rental sector can remain a little more competitive in the private rental market. But optimising the payment means more funding could be allocated to those who really need it.

2. A (bigger) boost to construction capacity.

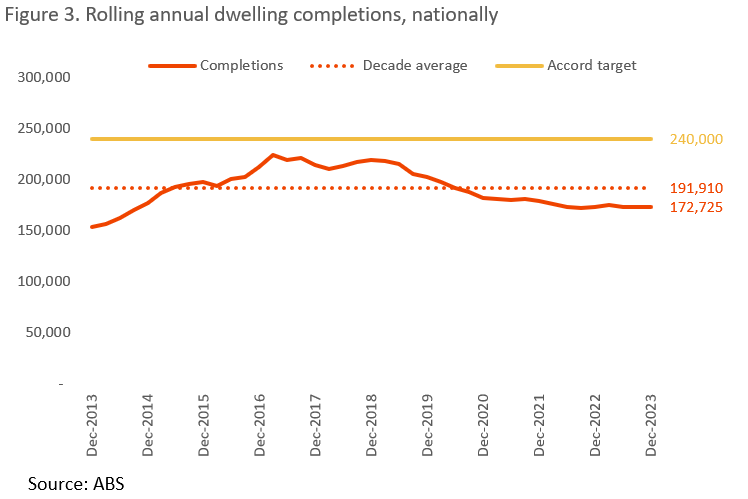

Australia’s construction sector is overheated, with too many projects stuck in the pipeline, and not enough feasibly-priced labour and materials to deliver them. The Cordell Construction Cost Index shows new house build costs are up 27.6% since the pandemic through to March 2024, and the new dwelling purchase component of CPI is up 36.1% in the same period. Our construction sector is so woefully stretched, we are unable to deliver homes at historic average volumes, let alone a stretch target of 1.2 million homes in a five-year period (figure 3).

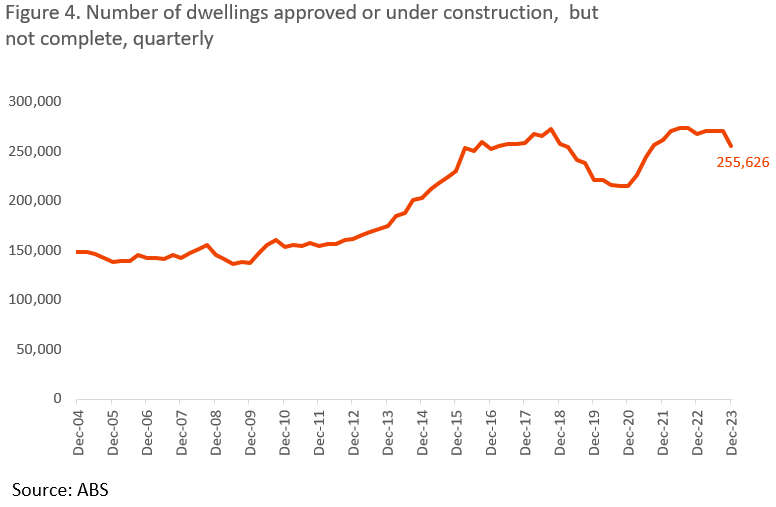

Project delays across both private and government-led housing projects are leading to a pile-up of potential supply in the pipeline (figure 4). The number of dwellings approved but not yet completed was 260,000 at the end of last year, which is actually higher than the annual accord target.

While lining up new projects to boost supply is well meaning, federal and state governments might be better off letting approvals continue to unwind in the short term amid high interest rates, so that cost pressures start to ease and the construction industry can focus on delivering the pipeline. This already seems to be working, with ABS producer price indexes now showing a reduction in the cost of steel inputs for residential construction, and the new homes component of CPI slowing to 1.1% growth in the March quarter, down from 5.7% in the March 2022 quarter. In the meantime, governments should focus on boosting the productive capacity of the construction workforce.

One way to reduce cost pressures is to beef up the construction workforce. The budget outlined around $91 million in training to do this, including:

- $62.4 million for 15,000 fee-free training places at TAFE and VET vocational colleges,

- $26.4 million for 5,000 pre-apprenticeship places, and

- $1.8 million to fast-track skills assessment for 1,900 migrants

This could add to labour supply to the tune of 22,000 workers, representing 1.7% growth in an industry where employment had an average quarterly increase of 0.7% over the past decade. But it is not clear when the additional workers would be added, with those just embarking on the start of training certificates and apprenticeships potentially taking years to become fully qualified.

A quicker way to boost productive capacity could be to focus more on already qualified migrant labour. Reduced levies for businesses to take on overseas migrant workers, and streamlining skills recognition are important structural reforms that need to be made across a range of sectors, but especially construction at the moment. Increasing female participation in construction is a focus of this budget (noting the announcement of the Building Women’s Careers program), where women currently make up an alarmingly low 14% of total construction employment in Australia.

Aside from labour, investing in research and innovation in construction processes would also help to boost productivity. Investment that helps to scale modular builds, and embracing technologies that can further streamline design processes are some examples.

3. Demand.

Aside from a more targeted, sustainable level of migration, this Budget missed an opportunity to shape housing demand. Bold tax reform on housing has the potential to increase government revenue, and shape housing demand so that our existing housing stock is used more fairly and efficiently, at a time when new supply is challenging to deliver.

In some ways, demand for existing housing stock is increasingly inefficient among some cohorts. In previous analysis we have noted that the portion of two-person family households in dwellings with four or more bedrooms was rising over time. Working with state and territory governments to introduce land tax as a replacement for stamp duty, or factoring in the family home as an asset in the aged pension test, are examples of policies that can shape the amount of housing demanded. ANZ Chief Economist Richard Yetsenga has also pointed to inefficiencies in a supply-led housing strategy, pointing out that with 11 million dwellings for 26 million people, we should also address the issue of misallocation of existing stock rather than overstating a genuine housing shortage.

This does not have to mean upsetting rental supply by scrapping negative gearing overnight. But there is room to modify the way we tax assets like housing. Chief economist at Westpac, Luci Ellis, suggested a redesign of capital gains tax, which could be constantly discounted by the long-term inflation target to reduce market distortion. While Ellis did not specify this being applied to housing, replacing the generous 50% discount on housing investments after one year could reduce short term resales of investment property that are prompted by short term capital gain windfalls, increasing stability of tenure for renters.

Like many before it, this Budget misses an opportunity to make meaningful changes that could make a fairer and more efficient housing system in the long term.