CoreLogic’s Head of Research Eliza Owen explains what buyers and sellers need to know about the coming downswing.

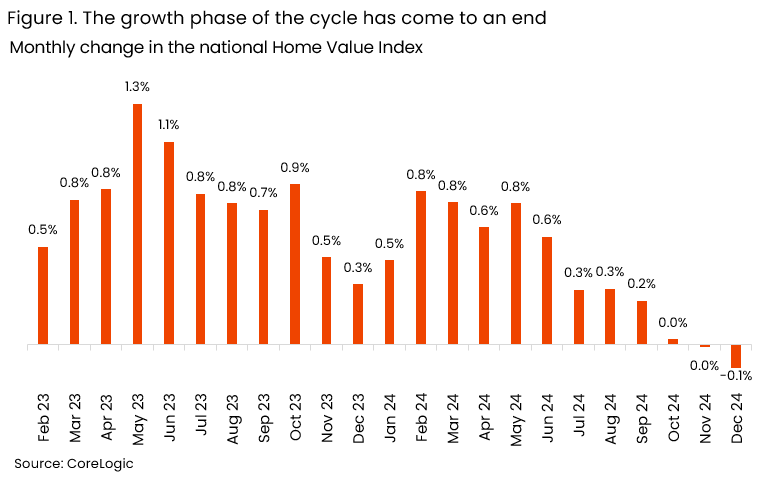

After 21 months of growth that pushed values up 14.3%, CoreLogic’s national Home Value Index (HVI) has finally recorded declines. After peaking in October, the national index steadied in November (-0.01%) and recorded a -0.1% decline in December. The start of a cyclical downturn is unsurprising, as monthly home value growth has slowed since June 2024.

The slowdown has been accompanied by other market shifts. Total listings levels across the country finished 2024 5.0% higher than a year ago. Selling times rose through the December quarter, up to 33 days from 28 days a year ago.

But is this cause for celebration among buyers? Should sellers be worried? Here’s what we know about the downturn so far.

Home values and interest rates are too high for buyers

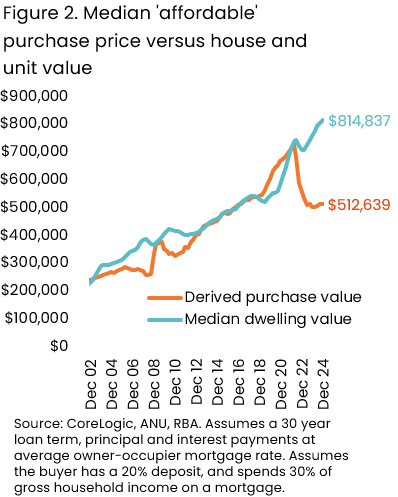

Housing demand has slowed amid a growing gap between income, borrowing capacity, and home values, exacerbated by slowing economic growth and ‘higher-for-longer’ interest rates. One way to look at this divergence is to consider an 'affordable' purchase price for the median income household in Australia, based on 30% of before-tax income spent on a mortgage, assuming current interest rates and a 20% deposit. This derived affordable price would be $513,000, while the national median dwelling value is $815,000 (Figure 2).

Historically these gaps converge as housing values drop or purchasing capacity improves through higher incomes or lower interest rates. For nearly two years, this gap may have been sustained by buyers less affected by interest rates, such as those using resale profits or higher-income buyers. Some buyers may have been willing to accept higher housing costs in the short term, on the expectation that interest rates would fall. However, as lower interest rates have not materialised, housing demand from these buyers may also be waning.

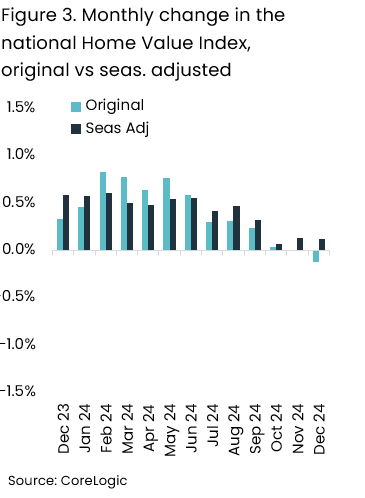

Seasonality at play, but housing values still on the way down

The first notable decline in home values has coincided with a seasonally slow period for the property market, when value changes are usually a little bit weaker. The seasonally adjusted HVI did not actually fall in December, instead rising 0.1%.

Australia’s housing market still looks weaker when accounting for seasonal effects though, and Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra still saw price falls. The national seasonally adjusted HVI has seen monthly growth slow to just 0.1% for the past three months, down from an average growth rate of 0.6% through the first three months of 2024.

The downturn is being driven by a relatively small number of markets, but that will change

In December, only five of Australia's 15 capital city and regional ‘rest of state’ markets saw declines. Melbourne had the largest drop at -0.7%, followed by Sydney (-0.6%), Canberra and Hobart

(-0.5%), and regional Victoria (-0.3%). Other regions saw increases ranging from 0.03% in regional NSW to 1.2% in regional South Australia.

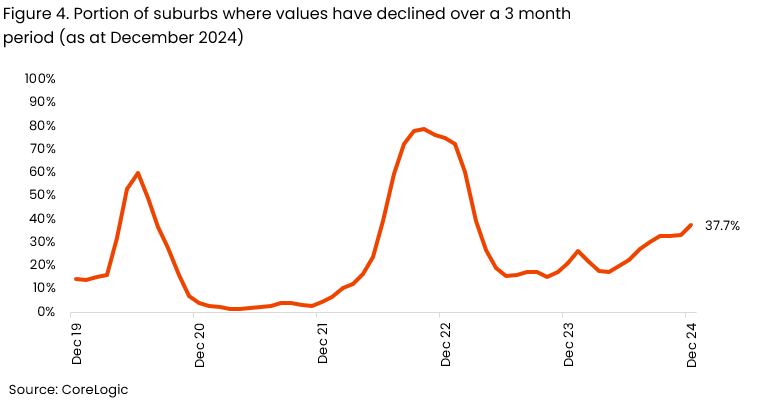

At a suburb level, only 38% of markets fell in the December quarter, causing a -0.1% drag on the national index, and Sydney and Melbourne accounted for 55.8% of these suburbs.

The national value decline is mainly due to Sydney and Melbourne, which account for roughly 40% of Australian housing stock, and 50% of Australian housing value. The HVI measures total value change without adjusting for market size, so movements in Sydney and Melbourne have a relatively large impact on the headline figure.

While the downturn is largely driven by Sydney and Melbourne so far, the general market trend is still experiencing a slowdown in most regions. Adelaide had the highest quarterly growth of the capital cities at 2.1% in Q4 2024, but this was down from 3.6% in Q3 2024, and a high of 4.1% in the three months to May. Declines are also spreading at the suburb level, with quarterly price falls up from around 20% of suburbs at the end of 2023 (Figure 4).

Will this downturn be large?

A cyclical downswing is likely for early 2025 but it may not be large. The largest recorded decline in the national HVI was only -7.7% from October 1982 to March 1983. At the national level, home value declines tend to be shorter and smaller than periods of increase.

Part of this is because sellers may be able to withhold their property from sale until values are rising, effectively restricting available supply during periods of price falls. This is dependent on the urgency of a sale, but labour markets remain tight and most mortgaged households appear to be coping with current interest rate settings, making a rise in forced sales unlikely.

Another reason this could be a relatively small market downturn is the tailwinds for property demand in 2025. Growth in real incomes may support more buyer demand as inflation moderates, and a reduction in interest rates would boost borrowing capacity. Underlying these economic factors is also a fundamental shortage of homes relative to the population, and the squeeze on the delivery of new housing amid weak capacity in the construction sector.

Given these factors, the downturn is housing values is likely to be shallow and short lived, but in the same sense, its hard to see any material growth returning to housing values, at least at a macro level, until housing affordability and loan serviceability improves more substantially.